German Federal Military and Federal Minister of Defence, Dr. Ursula von der Leyen

The Big Brother Award 2017 in the category Authorities and Administration goes to The German Federal Military (Bundeswehr) and the Federal Minister of Defence, Dr. Ursula von der Leyen (CDU) as commander-in-chief.

This year’s award marks the first time in the 17-year history of the BigBrotherAwards that we venture into military terrain, in other words, into an exclusion zone. Ms von der Leyen however has made an appearance before – in 2009 she received this anti-award in her position as Minister for Family Affairs. Under the nickname of “Zensursula” (censorship-Ursula) she was awarded for her foray into controlling content of and impeding access to websites. But how are the Minister of Defence and the military connected to surveillance, censorship, and data misuse in general? Why is the military in particular, with its tanks, bombs and grenades, an award-worthy data leech?

Well, today’s award is granted for the massive digital arms build-up of the federal military that is the “Commando Cyberspace and Information Space” (“Kommando Cyber- und Informationsraum”) – that means: for establishing a full-blown digital combat unit with a planned strength of 14,000, its own coat of arms, insignia and flag – even its own cyber march. There is already a small, secretive IT unit in Rheinbach near Bonn (“computer network operations”) of between 70 and 80 soldiers tasked with operative measures. This unit will be amalgamated with several other IT units, such as the Commando Strategic Reconnaissance, and centralised into the new cyber combat unit. Extensive advertising campaigns were started to attract new IT specialists.

This digital armament will open a new, fifth battlefield (besides land, air, sea and space), the so-called “battlefield of the future”, and will declare cyberspace – also known as the Internet – a new potential war zone. With this build-up of its cyberwar capability, Germany will take part in a global arms race in cyberspace – mostly without parliamentary oversight, without democratic controls, without legal basis.

This sounds somewhat worrying, but it remains rather abstract. What has all this got to do with us? What must we prepare for? Who will be affected? These are valid questions, but they are too limited. There are things that we won’t experience and suffer directly in this country but which can still cause harm or problems elsewhere. After all, basic human rights extend to people in other countries, who could well be affected – not to mention the potential escalation of this digital armament that may have a backlash effect; or the unsolved problems in international law.

It is, of course, a legitimate concern for the military to take appropriate protective measures to defend against foreign cyber attacks on its own military IT systems – allegedly thousands per day. But the Ministry of Defence is not satisfied with that alone. On the contrary: it claims – contrary to the rule of law, in our opinion – that the military should have co-operative responsibility for what it calls “pan-national security provision” and defence against cyber attacks. This includes the protection of other national, regional and civil networks within the country’s borders – but the responsibility for these in times of peace lies exclusively with the police, intelligence agencies and the courts, as well as the Federal Agency for IT Security (Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechik, BSI) and the National Centre for Cyber Defence. Domestic military operations for the protection of non-military IT systems from cyber attacks are therefore neither constitutional nor necessary.

But that is not all: its euphemistically labelled combat unit “cyberspace and information space”, commissioned by you, Ms von der Leyen, exactly one month ago today (05 April 2017) in Bonn, is not only tasked with defensive measures – your cyber warriors are also to be empowered to mount their own cyber attacks on other countries and their infrastructure. To put it bluntly: the intention is to wage cyber war – also as accompanying measures in conventional warfare abroad. This is outlined in the ministry’s 2015 secret Strategic Guidelines for Cyber Defence (Strategische Leitlinie Cyber-Verteidigung) and also in the Whitebook of Security Policy and the Future of the Federal Armed Forces 2016 (Weißbuch zur Sicherheitspolitik und zur Zukunft der Bundeswehr 2016). This means that the military shall develop their own arsenal of cyber weapons to be able to covertly break into foreign IT systems and use security vulnerabilities, trojan horses, viruses, etc. to be able to spy on, manipulate, control, disable, damage or destroy them.

But even if this is not considered an act of war in and illegal under international law in itself, but seen as the application of cyber force for self-defence against foreign military attacks, such activities might be permissible under international law in principle but they would still be highly risky. Why? Because not only military targets would be affected but civil infrastructure as well, at least as “collateral damage”. Cyber attacks, even if only targeting military installations, can spread like wildfire when they reach critical civil infrastructure, and disable or even destroy it. In a networked world, digital weapons are not precision weapons, and their scattering action can be extensive. The effects on the population can be grave if the attacks cause long-lasting disruption of electricity, water supply, or of medical, healthcare, or transport infrastructure. This would constitute a violation of international humanitarian law.

In addition to these effects of cyber attacks, a militarisation of the Internet will lead to further and almost intractable problems and threats:

First, there is a great danger that a wrong interpretation of a cyber attack as an act of war or a non-military attack might lead to premature self-defence action – and thus a dangerous and grave escalation. There is currently no clear and binding definition in international law under what conditions a cyber attack is to be considered an act of war. According to currently prevalent opinion1 among experts in international law, this is only the case when the destructive effects are comparable to those of conventional weapons – that is when online-attacks cause trains to derail, planes to crash, power plants to explode, and when people are injured or killed. But NATO as well as the German military explicitly reserve the right to decide in each individual case whether it is interpreted as an act of war, and what the reaction will be – “because we want to and have to remain unpredictable to a certain degree”, according to a lieutenant colonel at the Ministry of Defence2.

Second, there are no opposing armies in a cyber war, no soldiers in uniform. Instead, viruses, worms, or trojan horses are employed, in a covert and sometimes indirect way – software without uniform or national insignia. Data traces can be easily manipulated, obscured or attributed to someone else as false-flag operations to incite conflict or create a casus belli. Not only is it very hard to figure out whether IT attacks are civilian criminal acts and economic operations or executed by foreign intelligence organisations and the military, but the country under attack is faced with the problem of unambiguously identifying the perpetrator in order to react in a lawful, appropriate and targeted manner. Creating the chain of evidence is usually extremely difficult. The International Court of Justice requires clear evidence; there is no right to military self-defence as an arbitrary action or on the basis of circumstantial evidence; retaliatory action without a clearly identifiable aggressor is a violation of international law in any case.

Third, these problems are exacerbated by a dangerous legal interpretation in the “Tallinn Manual”, a NATO handbook for applying international law to cyber warfare (2013). Twenty legal experts mostly with close ties to the military, from NATO member states including Germany, have created these guidelines. Its 95 rules are supposed to serve as advice to NATO members in case of a cyber war, so they apply to the German military. But what makes these rules so dangerous? Here are three examples:

-

The manual classifies as cyber war attacks even such operations that only create economic and financial losses for the affected country, as long as they are of a certain magnitude, such as a stock market crash. The guidelines would then justify military self-defence, even with conventional means, which could lead to an uncontrollable escalation of the conflict.

-

According to the handbook, civilian hackers (so-called “hacktivists”) can be regarded as active combatants when they execute cyber actions in the course of armed conflict; this means they can be attacked and killed. Even searching for and publishing vulnerabilities in an adversary’s computer system would thus be considered an act of war. This effectively expands the combat zone to encompass civilians and their laptop computers.

-

NATO’s Tallinn Manual also provides for a right to a preemptive self-defence strike – even before any digital attack has occurred. As with conventional military first strikes there is a high risk of misuse and misinterpretation.

The legal interpretation in this NATO document lowers the high threshold in international law for military action between nation states to an irresponsibly low level and weakens the restrictive criteria for the right to self-defence. This is a substantial threat to the civil population and international security. What has been compiled here by influential experts on international law is capable of blurring the line between interior and exterior security, between civil and military matters, between peace and war, between attack and defence; and it allows for a swift escalation from a severe data attack into a real war with missiles, bombs and grenades.

The conclusion is that this armament of the German military for cyber war will increase the probability for escalation, the readiness and the real threat for a war to start – and the requirement for parliament to approve any military action won’t offer strong protection either. In the end, the minister’s cyber concept for the German military is hardly controllable by democratic means.

Although we present this award for evil plans and deeds, we never give up hope for our awardees and gladly grant them probation. This would require that you, Minister, step back from this digital arms build-up, renounce offensive cyber weaponry for the military and pursue a purely defensive cyber security strategy to protect the population effectively. This should be accompanied by trust-building measures within a peace-oriented foreign policy and diplomacy (“cyber peace”). Furthermore, we call for global cyber disarmament and international condemnation of cyber espionage and cyber weapons. We call for the creation of an independent United Nations agency for investigating inter-state cyber attacks and finding commensurate defences.

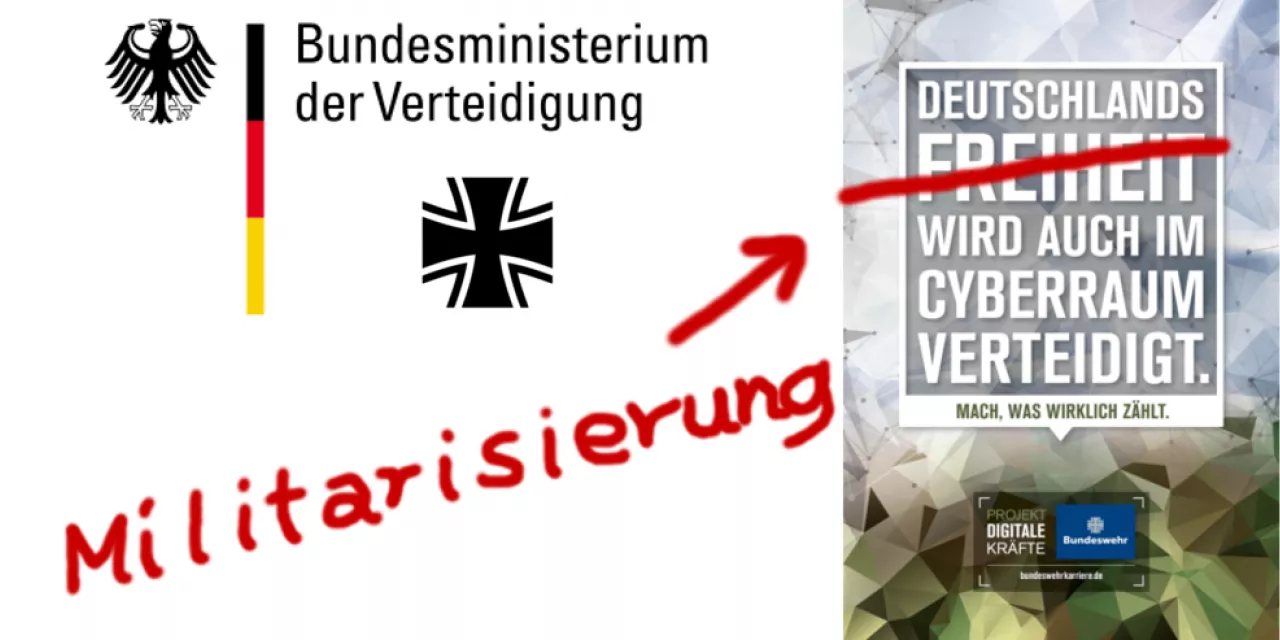

But what are you doing instead, Ms von der Leyen? You are, in your own words, “wringing your hands” in the search for “nerds”: “hackers, IT programmers, IT security specialists, penetration testers, system administrators or IT developers.” The military is said to have a need for some 800 IT administrators and 700 IT soldiers, that is, cyber combatants, per year. With a nation-wide large-scale recruiting campaign in railway stations, at universities and in the media the military is looking for experts and career changers. Civil experts from businesses, from associations and NGOs are courted to create a powerful “cyber reserve”. Following the war slogan “Germany’s freedom is also defended at the Hindu Kush” of your pre-predecessor Peter Struck, you have created the advertising motto “Germany’s freedom is also defended in cyberspace – do what really counts …”. That sounds exciting and possibly enticing.

Have you and your advertising team ever paid a visit to the Chaos Computer Club or Digitalcourage? In this hall tonight I’m sure there are lots of technophile and tech-savvy people perfectly matching your prey preference. And thus we really hope that this speech and our award ceremony will encourage these people to put their skills to work for peace and understanding in the Internet, instead of wasting them on digital attacks and cyber warfare on the “battlefield of the future”!

Congratulations for this negative Big Brother Award 2017, Ms Minister of Defence and commander-in-chief of the German Federal Military.

- Keine Reaktion aus Bonn oder BerlinUpdate zu BBAs

Laudator.in

1 E.g. Robin Geiß, Völkerrecht im „Cyberwar" (Web-Archive-Link)